Un-Digging Plot Holes

Questions to ask yourself on a first read-through to see if that story still makes sense

We’ve talked a little bit about the plot so far in Big Picture Character Arcs and when we talked about making a big idea small but plot ought to have its own section.

I often forget about plot in revision, ironically, because it’s where I start. I’ll say over and over again, I don’t begin a draft until I know how it ends. That doesn't mean I know where the story starts. The scenes that most interest me are often toward the middle. The first big turning point, a highly emotional escape, a really cool magical thing.

So my basic outline is connecting this inspiration scene forward to the end and then backward to the beginning.

For example, I had a smutty idea about a shy witch who visited/seduced a wolf-shifter in his dreams. The guy surprised her by having more control in the dreamscape than she did. It was a fun scene and very sexy, but I felt there was more to that story. So I sat down with the idea (or more likely took a walk) and tried to figure out who these two were, how they got into this situation, where their romance would lead. By the time I was finished, I had a plot that was a retelling of Rapunzel, including my character arcs for both the escaping daughter and her wolf-shifter boyfriend. I typed it up as an outline and I have no memory of ever deviating from that outline, because either I perfectly stick to all outlines and write an absolutely perfect first draft or I don’t remember the agony this particular novel put me through. To let you know which is more likely, I have a terrible memory.

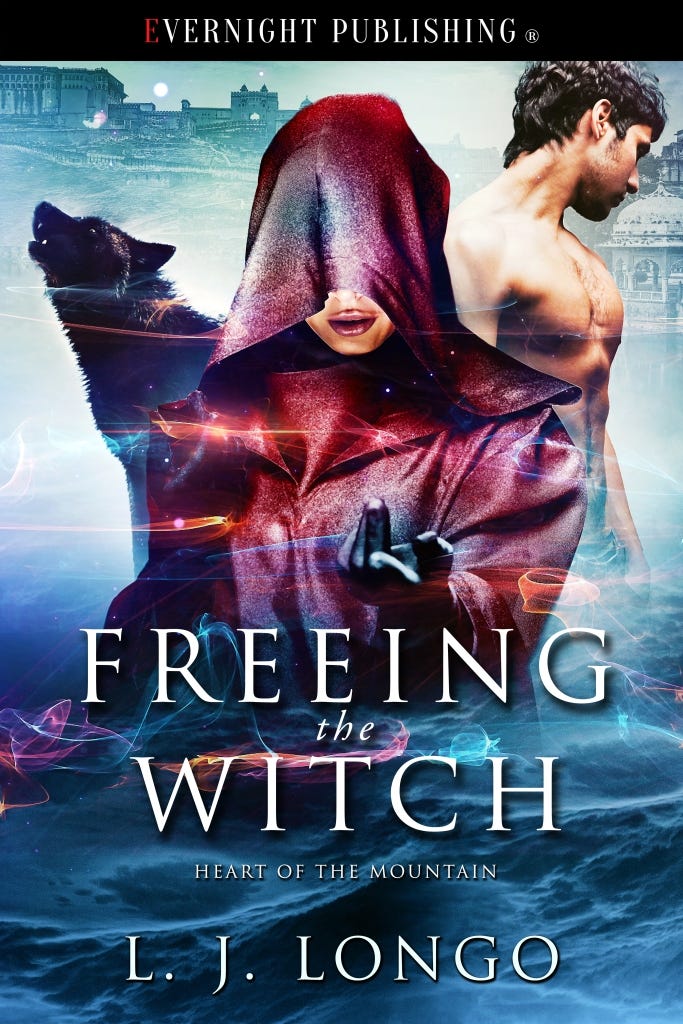

By the way, that novel is called Freeing the Witch and it’s available through Evernight Publishing.

For me, plot is an early building block, even more than character. So, in my first read-through, I make sure that the plot still makes sense and I haven’t dug myself into any plot holes by periodically asking these questions.

Is there a Logical Flow to the Events?

Real life is random; fiction is not. Readers expect not only that one thing to lead naturally to another, but that the events of each scene will be the consequence of the ones previous.

One of my favorite ways to talk about this comes from one of the creators of South Park, Trey Parker.

The story happens because there’s a causal link between two events (therefore) or an interruption in the characters’ goals (but).

Little Red Riding Hood doesn’t happen to meet a wolf, she meets the wolf because she is motivated to go to Grandmother’s house. She talks to the wolf, therefore she leaves the path which gives the wolf the opportunity to eat Grandma and then Little Red. But a woodcutter hears the wolf snoring therefore he cuts them free and kills the wolf. And then Little Red takes another trip into the woods wiser now from her past experience. Therefore she doesn’t talk to the second wolf or leave the path. But the wolf follows her to Grandma’s house. Therefore Grandma teaches Little Red how to lure a wolf to its death and protect herself. Therefore Little Red goes home safely and merrily.

That’s the full story of Little Red Riding Hood. Chances are you’ve only heard the first half. There are probably a million reasons why the story is usually shortened (the second part is repetitive and violent, the first is a complete story unto itself, male editors see themselves as savior and don’t feel the need to include the idea of a girl learning to save herself).

But I can’t help but notice in the logical progression of this story the break happens when the one and only and then that came up.

When I see a section where everything briefly wraps up and the next section has this and then feel to it. I try to find a way to overlap of bridge those moments.

Or since I write stupid long things, I mark it as a potential place to end an arc or section of the serial. That way an audience will not feel it as a lull in the story, but as a breather for themselves.

Coincidence? I Think Not!

In real life, sometimes you just happen to be in the right place at the right time. Or get help from exactly the right stranger. Unless you’re writing a story specifically about destiny (or are in a genre that forgives this kind of thing), too many coincidences and convenient solutions take the reader out of the story.

A coincidence is a great way to begin a story, but a terrible way to end one.

Oftentimes, something that feels coincidental can be fixed by either foreshadowing it or leading readers to it. One of the most satisfying things about a mystery is when you realize you’ve been given all the pieces to the puzzle and they come together before your eyes. If all the pieces are withheld until the detective has his monologue and puts all the pieces together, it’s not enjoyable because you’re watching some blowhard talk about how smart he is when he hasn’t let you look at the clues.

Why Wouldn’t They Just Do…

In your enemies-to-lovers romance, can one of your characters just walk away from their enemy rather than suffering their presence? Why don't your teenagers being chased by a serial killer call the cops? When the girl is tied up on the railroad tracks why isn’t she trying to worm her way off the tracks?

Have you done the work to narratively trap characters?

We make fun of action films for doing this all the time. Why do villains construct elaborate death traps instead of just shooting the good guy? Yes, it’s needed for the story because we want to see 007 or Batman escape. But it doesn’t take long to at least try to explain. Goldfinger has some appointment he needs to go to, so he leaves Bond alone in the room. The Riddler has a compulsive need to outwit his nemesis in a game.

Speaking of villains, do your antagonists have a character besides just obstructing the main characters? This might be a taste thing, but I don’t love villains who are evil just for evil’s sake. I’ve personally never met anyone who actually goes out of their way to kick kittens for the sheer joy of it (met a lot of people with anger issues who would kick a kitten in their way, though).

But readers love antagonists who act like the hero of their own story. So give your baddie a sense of honor or justice. Tie their survival to the thing the hero is trying to stop. Even if they are motivated by something ‘evil’ like power or money, give them a reason that makes readers say “there but for the grace of god…”

Most importantly, have their actions make sense. I love to see fantastical monsters running from fights, because in a logical world if you hurt an animal, especially a predator who is not used to being hurt, it flees.

Give human antagonists the same motivation. If narratively you need a fight between Mom and Main Character, build the tension between them so the fight isn’t coming out of nowhere and doesn’t feel like Mom is just an evil bitch. If the ex-boyfriend is going to disrupt a romantic date, you’ll need to explain to readers how this guy knew his ex would be in this cafe. They can’t just bump into each other.

Is it the only cafe in town? If they live in a city with twenty coffee shops, maybe this coffee shop is special to her (increasing her backstory) and she won’t be driven out by her ex (reinforcing her character) who haunts the place because he knows he will see her there.

Or maybe he’s stalking her social media (foreshadow by showing our girl posting her location frequently)

Or maybe he’s using dark magic, (actually, you’d probably mentioned that by now).

My point is, look for moments in this draft where the main character (or the villain) has an easier solution to their problem and is not taking it. Then explain why they aren’t taking the easy way. Or rewrite to further complicate the characters.

And because I’ve gone too long without a bulleted list in this article, here’s all those questions rounded up:

Do events flow from scene to scene in a logical, causal way?

if not is the coincidence explained

Are there coincidences that are not

explained

foreshadowed

shown to the readers to heighten tension

Are my characters behaving logically?

If not, is it justified, foreshadowed, or explainable?

Have I done the work to narratively trap my characters in their bad choices?

Why aren’t they taking the easier way out?

Why is the miscommunication not cleared up?

Does my antagonist have access to inhuman knowledge or power (ie. me moving the plot along) to antagonize my characters?

Can I explain, foreshadow, or justify this in text?

Are there any boring bits I can make better?

Over the next couple of months, Lane and I are going to be working on a book together. My plan with this section of the substack is to write about that journey from the opening outline to the finish and then through the revisions. If that sounds like something you want to see, make sure you are subscribed!

And if you’re looking for a professional developmental editor or a book coach, I’m on Fiverr!