The Hero Quest vs The Heroine's Journey

A death match to see which of these gender structures is superior! Or... how they work together in long works and really compliment eachother.

Lane and I took a break from life last week due to a combination of life events (we got a brand new car!) and illness (we got the flu!), but during that time we played a lot of video games (God of War (2018) and God of War: Ragnarok (2022)) and listened to Mike Duncan’s podcast about The French Revolution.

Somehow, they went really well together and got Lane and I talking, in a fever dream, about structure and particularly about The Hero Quest vs. the Heroine’s Journey. Mostly because both of these stories fail to be either a Hero Quest or a Heroine’s Journey.

Obviously, one is a podcast about real history and so cannot be blamed for not following narrative structure (get your shit together, Revolutionary France!). But Mike Duncan does an incredible job of detailing this history in a long story that constantly feels like a tragedy for the individuals in play. I kept routing for people who are about to die to somehow miraculously escape and save the country and their ideals (spoilers: they do not).

The video game took us on such a great and exciting adventure that we talked about it for days the whole time we were playing it. Then suddenly, something rerailed in the final act and both os us felt a little unsatisfied with the storytelling. There’s a couple of reasons for that I hope to get to one day (maybe an article about writing world-ending stakes and the dangers of having a complicated villain), but the one I want to talk about here today is getting stuck between telling a Hero’s Quest and a Heroine’s Journey.

Let me start by talking about those structures on their own:

The Hero Quest

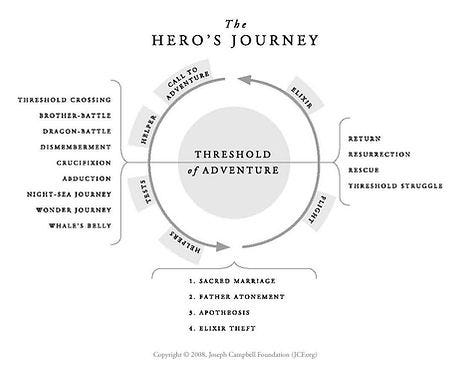

Academically older and more famous of these two writing structures is The Hero Quest. It was originally written down as a way to interpret and analyze myth by the brilliant scholar Joseph Campbell. In his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), Campbell explains it this way:

“A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

I love this guy and I think The Power of Myth and Hero with a Thousand Faces are not just excellent books about literary criticism and understanding mythology, but also give a good roadmap to a well-lived life. Joseph Campbell is the guy who wrote, “Follow Your Bliss” which if I was less practical I would have tattooed somewhere on my body.

Campbell’s basic structure probably looks familiar to you:

A reluctant hero receives a call to adventure and leaves his ordinary world. Guided by a mentor, tested by supernatural forces, tempted by maidens, he battles dragons, spends some time alone in the belly of the whale, before eventually being reborn, winning (reaching divine enlightenment), getting some treasure, and returning to the ordinary world changed and blessed.

This feels like a really blithe sum-up because I assume most writers have encountered the Hero’s Journey. If you haven’t, many others have written about it in more depth than I’m going to give it here. I highly recommend Christopher Vogel’s, “The Writers Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers” or check out this much shorter video: What makes a hero? - Matthew Winkler

Here are the basic steps:

The Ordinary World: Introduces the hero in their everyday life, establishing their normal routine.

Call to Adventure: The hero receives a call to leave their ordinary world and embark on a quest.

Refusal of the Call: The hero initially resists the call due to fear or uncertainty.

Meeting the Mentor: A wise figure provides guidance and tools to help the hero on their journey.

Crossing the Threshold: The hero commits to the adventure and enters a new world.

Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero faces challenges, meets allies who support them, and encounters adversaries.

Approach to the Inmost Cave: The hero gets closer to the ultimate goal, often facing increasing danger.

The Ordeal: The hero confronts their greatest challenge, a moment of ultimate crisis.

The Reward: The hero overcomes the ordeal and receives a valuable prize or insight.

The Road Back: The hero begins their journey back to their ordinary world, often facing new obstacles.

Resurrection: The hero experiences a final test or near-death experience, demonstrating their transformation.

Return with the Treasure: The hero returns home, changed by their journey, and shares their newfound wisdom or power with others.

This feels like a tool for writing a fantasy script, but any departure from the ordinary world can be a life-changing journey.

For example, I could tell a story about a little girl who wants to play video games but her mother insists that she go ride her bike around the block. At the corner, she meets a slightly older girl who tells her there’s a candy store down the way and our girl says, “I’mma steal a chocolate bar.” So she crosses the big road. An adult stops her and asks why she’s alone, she gets scared by a hug rat, and turns down the wrong street and races out of control down a hill where her training wheels get smashed. Lost, alone, and without her trusty bike, the girl grieves her choices, wishes she was home, and hates her sweet tooth. Then after her tears, she tries again to find her way home. Putting up the shaking training wheels, she rides the bike again, wobbly at first but then with confidence back up the big hill. She recognizes the candy store and the owner gives her a bag of sweets because she is riding without her training wheels all by herself and she returns home, sharing with the older girls on the way, and when her mother says she can come in and play on her tablet again, our girl determines she wants to play outside some more.

Cute story. Follows the hero quest.

I’m the kind of nerd who can spend all day thinking about movies and books and putting them into this or that formula. It’s another technique to make a synopsis of a longer work, as well.

But what if it doesn’t fit this outline? Let’s talk about The Heroine’s Journey.

The Heroine’s Journey

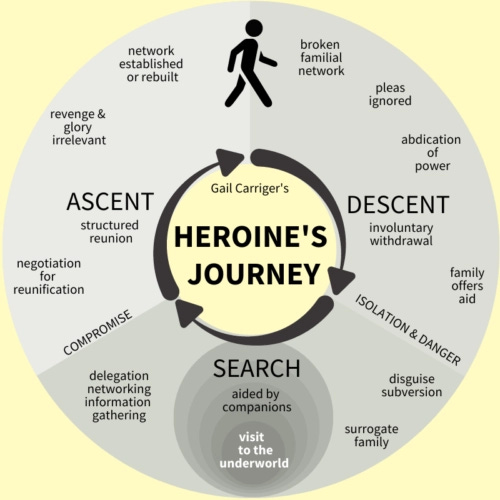

A psychotherapist who studied Joseph Cambell, Maureen Murdock came up with a more feminine-focused template. She described it as: "The feminine journey is about going down deep into soul, healing and reclaiming, while the masculine journey is up and out, to spirit."

Gail Garriger wrote, The Heroine’s Journey: For Writers, Readers, and Fans of Pop Culture, which takes Murdock’s ideas and applies them to fiction. If the hero’s journey is about how to overcome fear; the heroine’s journey is about how to create connection. It’s just as common in media and myth and does not have to feature female or female-coded characters.

Here is Carriger’s basic structure:

A heroine is separated from her family, her attempts to heal this are ignored and she withdraws from society and safety to search for a way to recover her family. In the underworld, she begins to make friends, forge connections, and build up a community that will help her confront her problem. She is seeking peace, unification, and justice (and safety) for all and returns to society with a new family connection.

So this is the found family trope, but also most romance novels and a lot of YA. You’ll start to see it everywhere once you start looking for it and as Gail Carriger points out, like the Hero’s Journey, it is not gender specific. A man can go on the heroine’s journey and a woman can go on the hero’s journey we just have gendered names for these two myths to work with right now.

Here are the basic steps:

Act 1: The Descent into the Underworld

Descent precipitated by a broken familial network.

Heroine’s pleas are ignored, and she abdicates power.

Withdrawal is involuntary.

Family offers aid but no solution.

Act 2: The Search

Heroine’s loss of family yields isolation/risk.

She employs disguise/subversion and alters her identity.

She appeals to and forms a surrogate network (found family).

She visits the underworld, aided by friends/family.

Act 3: The Ascent in the Living World

Success in her search results in a new or reborn familial network.

This ties to negotiation and compromise that will benefit all.

Once again, due to its mythic origins, this feels like a tool for speculative stories, but the underworld can be mundane.

For example, I could tell a story about a little boy who has just moved to a new neighborhood. He misses his old neighbors and only takes comfort in his pet rat, Mochi. One terrible day, Mochi escapes while they are at a park at the bottom of a hill. Mom is uninterested in helping our boy find his beloved pet (she thinks it’s kind of weird he keeps a rat) so it’s up to the boy to find Mochi. He goes outside and begins his search by riding his bike to the bottom of the hill, where he spends a lot of his time hiding in alleyways to keep himself safe from strangers and his mom who is looking for him. When he accidentally scares a girl with a broken stabilizers who thinks he is a huge rat, the boy helps her fix her bike and she joins him in his search for the rat, suggesting that they use some treats from the local candy store to lure the rat. At the candy store, he tells the story of how he met Mochi and the candy store owner is so moved she starts a call to the neighbors to bring in all the cats to keep Mochi safe. Other kids and parents start to flood out into the street looking for Mochi and helping our boy. Even Mom joins, apologetic for dismissing her son’s real feelings for his pet. When Mochi is recovered safe and sound there is a party in the park that turns into a monthly cookout.

Cute story. Follows the heroine's quest.

If your story fits into one of those structures you’ve got a good story with a solid base. But what if it combines both? What if it fails at either?

Failing the Journeys

Tragedy makes for a very powerful story and disrupting either of these mythic journeys leads to nothing but pain. One of the reoccurring things in the French Revolution (or at least in the way it was told by Mike Duncan) is how close the revolutionaries came, time and time again to make their ideal democracy work. Frequently petty squabbles, power-plays, and war-mongering got in the way. No one man was e unable to individually force his will and slay his dragon (hero quest) and as a unit they were also unable to unify because they became obsessed with revenge, glory, and the guillotine. History is not as simple as all that, but Duncan kept a compelling narrative going by framing each story with ebbs and tides of hope, unity, and eventually destruction. I remember once when he was focusing on King Louis, I was seriously willin,g the man to make the right compromise, the right alliance and finally get his family to safety, even though I knew damn well things do not end happily for the royalty in Paris 1793.

If you are writing a longer work (because I hope you will end things happily), see if there are moments along the way where one of these journeys fail. Sometimes the journey needs to be restarted with more humility, but other times it morphs into the other type of journey.

Merging Both Journeys

I first noticed this with LOTR. The first part of that trilogy is all about building unity. Hobbits, humans, dwarfs, elfs, and whatever Gandalf work together to form the fellowship and confront the villain. It’s very much the Heroine’s Journey.

But soon this unity fails them. Disaster separates the Fellowship and Frodo makes the choice to go on alone. Even with Sam along, the influence of Gollem and the One Ring plunge Frodo into his own internal darkness where he trusts no one and is deeply, deeply alone. Frodo moves on in the hero’s quest confronting the inner darkness, overcoming evil, and returning home transformed and unable to fit back into hobbit life.

It can work the other way, too. Think about all the stories where you have someone struggling to defeat some evil by themselves and failing until they learn to rely on their friends and their team. Maybe there’s a reason the heroine’s journey starts in a place that looks an awful a lot like “the belly of the beast”.

I love seeing these two journeys in conversation with each other, but it can get tricky. In the two God of War games based in Norse Mythology, Kratos (who wiped out the Greek pantheon brutally in God of War 1 through 3) is raising his son, Atreus, and dealing with his legacy of violence.

In the first game, the two are on a pretty straightforward hero quest to spread Kratos’ wife’s ashes on the tallest mountain in all the realms. They receive boons and guidance from several characters, there are a couple of deaths and resurrections (in the story, I mean, not just because it’s a combat game), they get in and out of hell, learn more about who they really are (esp. the kid) and eventually, they achieve their ultimate goal and are wiser, stronger heroes.

But because all along it was the two of them working together and healing the breach of Krato’s emotional distance, it’s also functioning as a heroine’s journey. They are reunifying their family during this quest, healing from the death of a beloved wife/mother. They adopt the mentor and after cutting off his head add him to their family unit (it’s a great game). They very nearly bring a goddess into their party, but fail to achieve this because they cannot form a compromise with her son and end up with her as an enemy. The first game ends with a beautiful moment of connection between father and son and enlightenment.

The second game, God of War: Ragnarok, has the same balancing act, but starts to fall down in the middle. Atreus is on his own hero quest, in defiance of his father (sort of, Krato’s motivation gets a little hard to follow), and on a path to confront Odin and liberate the realms from the Asgardians (the villains). They spend the first part of the game working hard to amass allies, forming a tentative peace with that goddess from the first game, freeing another god to aid in their fight. This could have easily morphed into a heroine’s journey with Kratos and Atreus working together to unite the realms, but instead, we got a story that was about rejecting destiny, but also accepting destiny, or maybe ignoring destiny and insisting it was ‘our choice’ not fate? They stop following the hero quest (Kratos is determined not to go to war with Odin to save his son) then the unification of the other realms happens off-screen and it’s other characters who do it.

Once Ragnarok starts again, the plot gets back on track and we get a return to the sweet combination of two heroes overcoming their obstacles in a big and epic way, that also combines elements of the heroine’s journey by bringing people together in hopes of a long-standing peace and unification. But both Lane and I felt kind of let down by it. We felt de-railed in the middle because although characters were still taking action and killing baddies, we weren’t sure why anymore. I think because we weren’t following either journey and so motivations got hazy.

Now, this game won like a bajillion awards, is widely regarded for its excellence in story-telling, and was a damn fun game to play/watch. It might just be that my husband and I are real pretentious asshats. Also, fantastic character growth:

But, if while I was re-reading a draft of something I’d written, and I felt the characters were struggling too long to make a choice or acting with flimsy motivation, I’d look into the structure. Pinpoint where your characters are in their mythical journey and see what’s stopping them from getting to the next part. Maybe they need to be knocked down to the pit of despair again. Maybe they need a reminder that the villain they are facing is a real dragon that threatens everything good. Maybe they’re doing too many side-quests…

Over the next couple of months, Lane and I are going to be working on a book together. My plan with this section of the substack is to write about that journey from the opening outline to the finish and then through the revisions. If that sounds like something you want to see, make sure you are subscribed!

And if you’re looking for a professional developmental editor or a book coach, I’m on Fiverr!