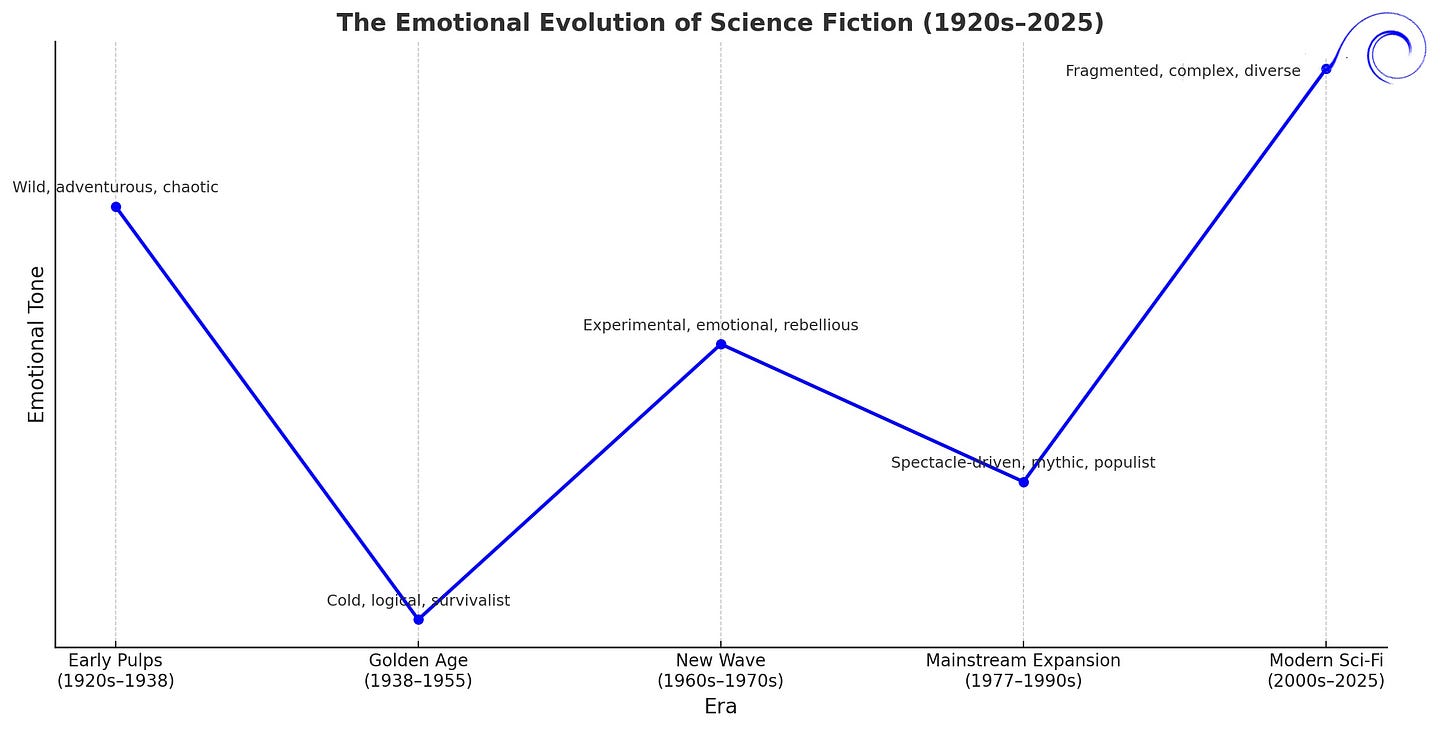

I’ve long been fascinated with the relationship of fiction to the work that comes before it. Influences, inspirations, rejections. I think the philosophies call this “discourse.” Science Fiction has an interesting relationship to itself, because so much experimental and original sci-fi draws not only from the sci-fi that came before, but also from the real technologies, real political movements, and often credible predictions of the future. But sci-fi is also interesting, because it’s one of the few genres that has a “tone” attached to it. During the golden age of Sci-Fi, a detached, unemotional tone was so prevalent and so often imitated that even writers today are working against that legacy. This is an exploration of that tone, how it came to be, and its enduring legacy in a genre defined by experimentation.

Modernism and the Pulps

A little bit of background first. The world is at war. The first time.

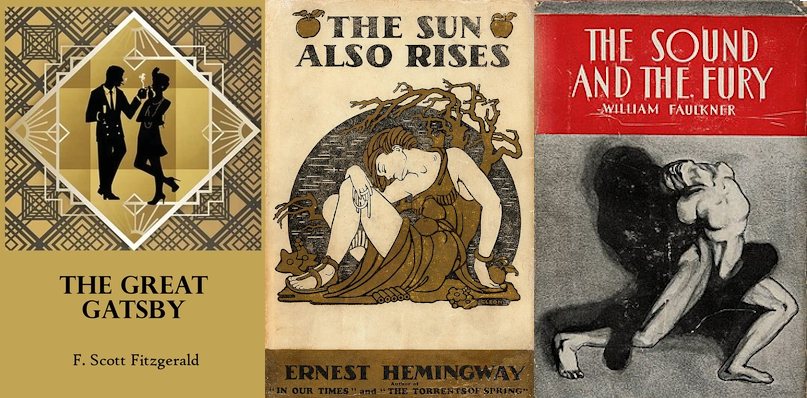

The artistic movement that sweeps the literary world is called Modernism. Dominated by themes of personal isolation, disillusionment, and the devastating cost of survival, this is one of the bleakest periods in fiction. Virginia Woolfe, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Ezra Pound, Earnest Hemingway, Marcel Proust, William Faulkner, G. Scott Fitzgerald, D.H. Lawrence, and Franz Kafka are all writing in the aftermath of World War I, though the rapid industrializations of their societies, and the economic and social collapses lead up to World War II. The whole movement can be summed up by W.B. Yeats’ The Second Coming with the line “Things fall apart; the center cannot hold.”

The experimentalism of these works redefined the literary landscape and created techniques writers of genre fiction still use today (like stream of consciousness, natural dialogue, and more relaxed grammar). But it also begins the divide between “real” literature and escapist stories. Serious work was printed on good paper, bound properly, and displayed in the home. The pap of the masses was printed on cheap, low-grade paper, expected to fall apart as you passed the magazine around to friends and family and eventually threw them away. These were called pulps.

Before the pulps (back in Mary Shelley’s day), all speculative fiction was amorphous. This was the time before real genre categorization, so stories like Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, A Christmas Carol, Treasure Island, and Dracula, all infinitely identifiable a genre pieces today, were sold and on the same shelf as the realism. But as people grew more and more literate and publishing became easier and cheaper, readers began to ask for specific kinds of stories. Categories began to emerge to feed the voracious appetites.

Early pulps were almost always crime, romance, and westerns. Sci-fi didn’t get its rockets lit until the 1920s with Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories.

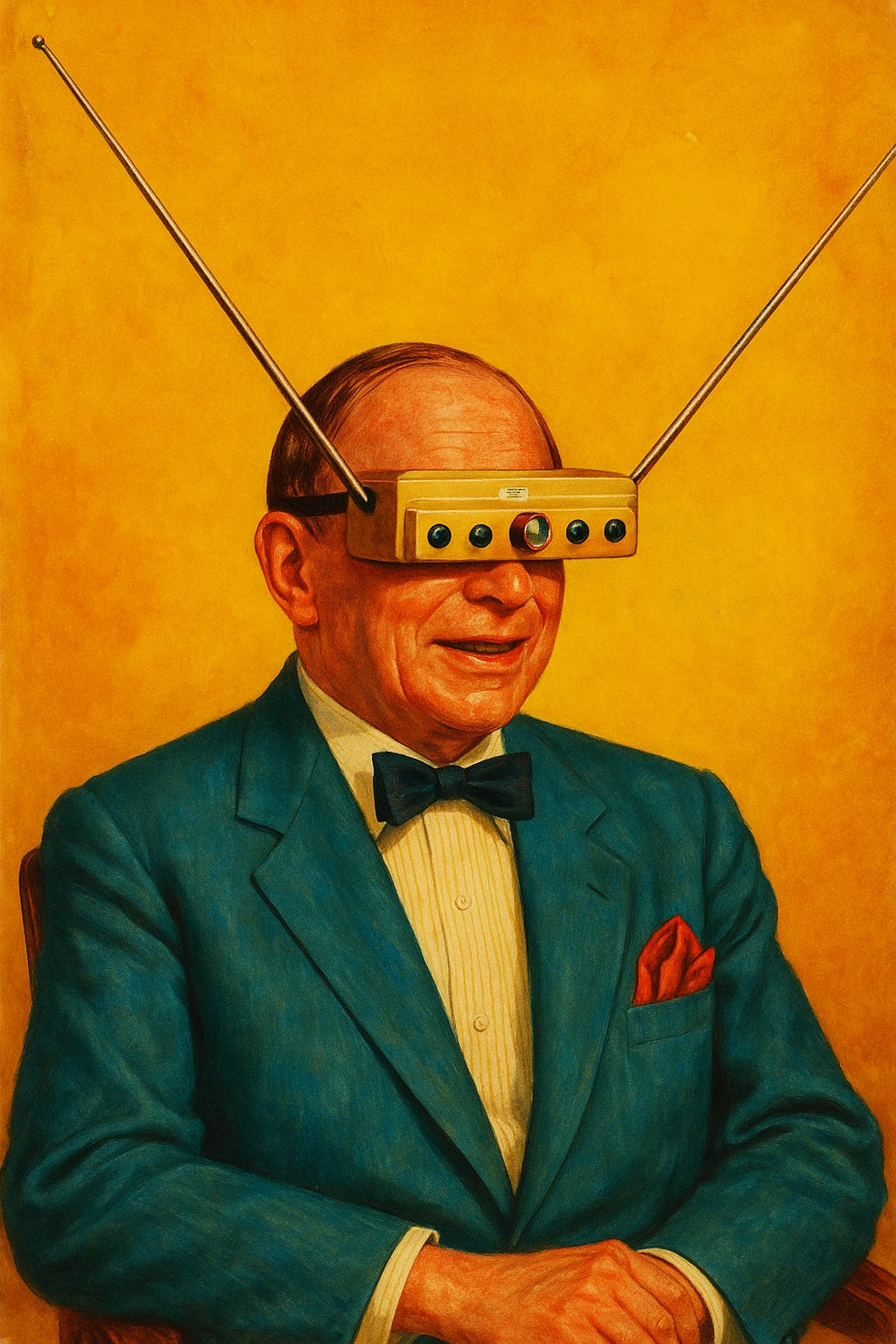

In these early days of sci-fi, magic and technology are interchangeable. The scientification of these stories was based more on imagination, mythic tropes, and basic science education than hard facts, but it still was obsessed with technology and all the faster, bigger, shinier things those mad scientists could create. Just look at the worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs (John Carter of Mars) and Robert E. Howard (Conan the Barbarian), who freely mix sorcerers and spaceships in a pure adventure. Women like C.L. Moore and Leigh Brackett (who would later co-write The Empire Strikes Back) were also among the pulps' brightest stars, blending horror, romance, and myth before genre boundaries hardened.

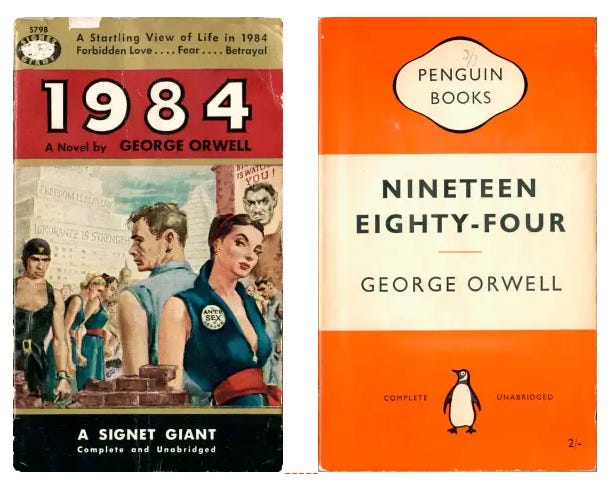

As World War II marched through, bleakness dominated the wider literary world. While many pulp writers made money launching adventure tales at astonishing speeds, it was writers like George Orwell who were earning glory and prestige for cautioning the end of the world, the collapse of freedom, individuality, and truth.

It’s clear from these covers that even in its first publication, high-quality literary art that also happened to be speculative was at the beginning of an identity crisis.

“Serious” storytellers wanted to move away from the melodrama and flash of the pulps. They didn’t want to be scintillating, easy, or disposable. And since the authors of the Modernist movement were being printed with hard covers and sophisticated covers, their style became associated with literary quality. Emotional restraint, dry prose, and limited internal thoughts signaled stories suited for proper, educated adults.

So it’s no wonder that the cold, logical tone and atmosphere of early science fiction blooms in a mushroom-shaped cloud during the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

Golden Age of Sci-Fi

From 1938 (John W. Campbell editing Astounding Science Fiction) to the mid-50s, science fiction gets hard. Tone and atmosphere deeply match, so when these writers are crafting cold, sterile environments, they are also building cold, logical narrators/characters. Arthur C. Clarke (2001: Space Odyssey) and Isaac Asimov (Foundation and I-Robot) both have characters that are frequently logical to a fault, or at least more interested in the progress of science and machines than in human beings. And writers are still imitating these two giants of the genre.

Hard Sci-Fi frequently matches the cold, vast vacuum of space with the cold sterility of logic. A combination of the grim reality of survival in a world that was not designed for human habitation and a cast of characters that usually included traditionally emotionally repressed people (scientists, engineers, and God forbid, bureaucrats) meant early sci-fi had a tone and atmosphere of cold, sterile logic that matched.

Of course, this match in tone and atmosphere was never the rule. Ray Bradbury, a contemporary of both Clarke and Asimov, wrote science fiction that had tonal clashes. The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451 both feature desolate and surreal atmospheres, but are filled with deeply hopeful, even childlike characters. His characters are fueled by a nostalgia for humanity and connection, even as the world strips those away through automation, censorship, and distractions.

By the mid-50s, the cold-clinical tradition of early literary sci-fi was giving way to the warmer, more hopeful tradition that Bradbury represented. Frank Herbert’s Dune sat right at the crossroads with a tone and atmosphere that matched, but were extremely deep and layered. The planet of Arrakis is one of the most intense, merciless, and mystical environments in all of science fiction and the tone that matches it manages to be both intensely philosophical, reverent, and rigorously intellectual in explaining the science of world-building.

New Wave

, was a turning point in sci-fi. Herbert retained the Golden Age structure but opened the shuttle bay for the next generation of writers. The New Wave movement writers like Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, Harlan Ellison, Phillip K. Dick, Octavia Butler, J.G. Ballard, and Samuel R. Delany bucked the basis in real-worl science and delved into emotionality. They did weirder, more experimental stylistic things with their works (likely influenced by the realism canon as well as their revolutionary times). This generation of speculative writers mirrored their worlds but also allowed their characters to challenge and change them. They deliberately broke ties with old masters and pushed sci-fi to a focus on people, perception, and passion, not just the technology. I imagine the Civil Rights movement, feminism, the sexual revolution, and anti-war protests offered a lot of inspiration to these writers when it came to taking risks and pushing boundaries.

Speaking of boldly going where no one has gone before, Star Trek is smack dab in the middle of the New Wave period. There’s a fantastic contrast of the cold, vastness of space and the colorful– dare I say groovy– decor of The Enterprise. That duality is echoed in the characters with the warmth and passion of Captain Kirk contrasted with First Officer/Science Officer Spock.

I do not doubt that Roddenberry was a fan of both the early pulps and the Golden Age sci-fi and was creating a television show that could relish in the glory of technology and exploration while retaining the logic and love of science. Star Trek is Golden Age in its ambition– but New Wave at heart.

Star Wars to Today

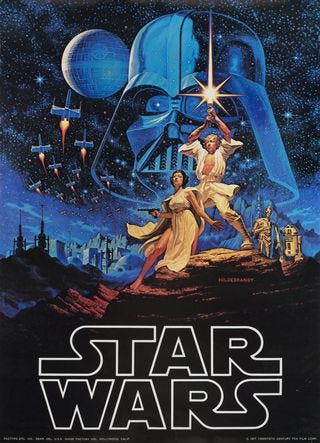

In the late 70s, sci-fi splintered into mainstream pop culture with a phenomenon that blended Sci-Fi with fantasy, western, and myth. A little movie called Star Wars.

Star Wars was a complete return to pre-Golden Age sci-fi. Like early pulp sci-fi, magic and technology live side by side. Many people will argue that Star Wars isn’t really science fiction, since there is so little science involved, but to quote my brilliant husband, “any definition of genre that removes the most well-known version of that genre is bullshit.”

Time-travel forward to today, where science fiction is an ecosystem of various styles. From Afro-futurism to Queer Weird SF with all the shades of Hopepunk and Grimdark in between, science fiction is weirder and more literary than ever. And, there’s a resurgence in hard sci-fi led by Andy Weir (The Martian, Project Hail Mary) and Cixin Liu (The Three-Body Problem). Both these writers are putting the science back into sci-fi; Liu harkens back to the formal, logical style of the Golden Age, while Weir is fully embracing emotional, voicey narrators.

So if you are a sci-fi writer, there is no need to tie yourself down to any one tone or style. Hope, horror, and survival are all still driving forces and can be expressed with matching or clashing tone and atmosphere. Science fiction today no longer promises either progress or apocalypse. It promises complexity — worlds where technology and human weirdness collide at lightspeed.

Over the next couple of months, Lane and I are going to be working on a book together. My plan with this section of the substack is to write about that journey from the opening outline to the finish and then through the revisions. If that sounds like something you want to see, make sure you are subscribed!

And if you’re looking for a professional developmental editor or a book coach, I’m on Fiverr!